O, wind, if winter comes, can spring be far behind?

Prologue

Last March, ZK and I took some of the pack for an exploratory of San Emigdio Mesa and lower Apache Canyon, focusing on the old Cienega campground. This area is (figuratively speaking) littered with abandoned camps — only about half the number of sites Forest-users enjoyed a generation or two past still stand. The San Emigdio (much of which is now part of the Chumash Wilderness) is easily — to my mind — the emptiest stretch of local Forest, a perfect place for when a bout of wanderlust forces one’s bootlaces to cinch up.

Earlier this year, we vowed to get more time in around our old haunts. But 1) a short snowshoe trip the week before the Cienega exploratory, 2) the annual Lily Meadows trek, 3) some late-spring foolery atop Mt Pinos, 4) a quick recon of the McGill Trail, 5) some Toad Spring exploratory, 6) a wind-blown visit to the Frazier Mountain lookout and 7) an exploratory of the old Ozena site (more on that later) had been our only Chumash-area visits this year. Not good enough — clearly we were doing it wrong!

And so it was last week that we assembled a larger-than-usual rag-tag team of hardened LPNF explorers for some Quatal and San Emigdio exploratory. But one by one — like the lost camps of the San Emigdio — each was forced to accommodate real-world obligations and bow out of this sojourn. And so once again it was left to the two red-bearded forest hermits who excel at ignoring their obligations to grab some eager canine assistance and head to this sage- and pinon-dotted expanse.

As part of the larger exploratory, we first reconnoitered the old Mud Springs and Blue Rock Spring campgrounds.

Both were never terribly impressive, I’ll admit … underwhelming sites are something of a hallmark of the former Cuyama RD sites later absorbed by the Mt Pinos RD. But don’t read anything into that; most of the lower-elevation Mt Pinos RD sites fall in the same bracket.

Mud Springs

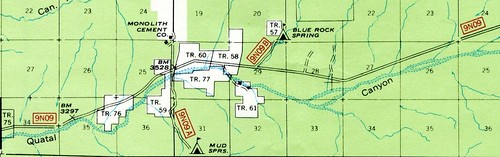

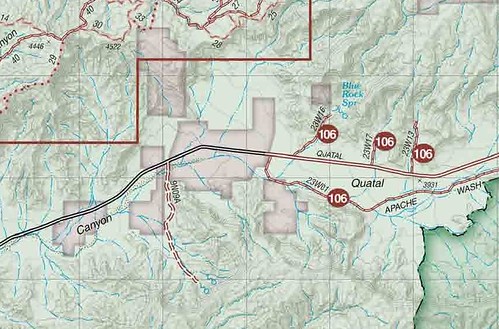

We approached the area from the 33, heading east up Quatal Canyon Road. After only a few miles a pair of old Forest routes split off — two of dozens of routes (many unofficial) that weave in and out of the main corridor. Forest Road 9N09A — a moniker given to a different road on the 1995 quads — leads south from Quatal Canyon toward Mud Springs.

The site proper was rather plain, but one still gained a great feeling of solitude standing here in the late morning. (As an aside, it’s these side canyons cut deep into the badlands that make it easy to forget you’re only a few miles as the condor once flew from the San Andreas Fault. The Chumash knew nearby Cuddy Valley as the “Trembling Land,” and according to Massey the moniker “San Emigdio” comes from St. Emidius, a German martyr believed to offer protection from earthquakes). So long as the folk who might occasionally come up here with their rifles and an old TV to blow up weren’t around, this would still make a fine weekend camp. There were two or three good spots for a tents — most beneath or beside scrubby oaks and thick pinon.

The first of the two springs shown on the map was easily found; a nice concrete box near the wash. The water was bone-chilling cold, so of course the dogs immediately approved and sought its healing qualities.

The second spring we didn’t spot immediately, and so we opted to take advantage of the cool climes and wandered down a few ravines. Following are a few rough video clips of our endeavor (and eventual success, though I use that term fairly loosely here).

Blue Rock Spring

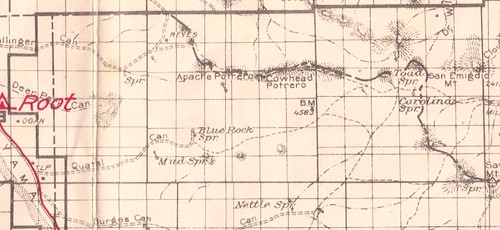

In the 1920s — when this stretch of land was known as the Santa Barbara National Forest — Blue Rock Spring was quite literally the end of the road.

That’s pretty difficult to envision now, as the old road — now one of many non-contiguous pieces of OHV Trail 106 — dead-ends a quarter mile or so from its namesake serpentine formation, and a fair portion of it runs right down the throat of the wash. If there was water of any measurable quantity therein, it’s not a place I’d be keen to place the truck.

The 2008 Pinos OHV maps show the route and spring well enough, but still offer no indication of the old site that once stood here. And like many of the “abandoned” camps we’ve discussed previously, just because it’s no longer officially recognized and no longer receiving funding/maintenance/what have you, that doesn’t mean folks aren’t still using the sites.

Blue Rock Spring is another good example of this. The main flat where we parked has two (perhaps three) suitable camping spots, and further up the road to the northwest was another flat that had certainly been graded in decades past. No shade there, but space a’plenty.

From the depths of Quatal Canyon, we headed up to Toad Spring and Mt Abel for additional exploratory; more Cuyama/San Emig/Chumash reconnoiter reports coming soon.

Leave a Reply